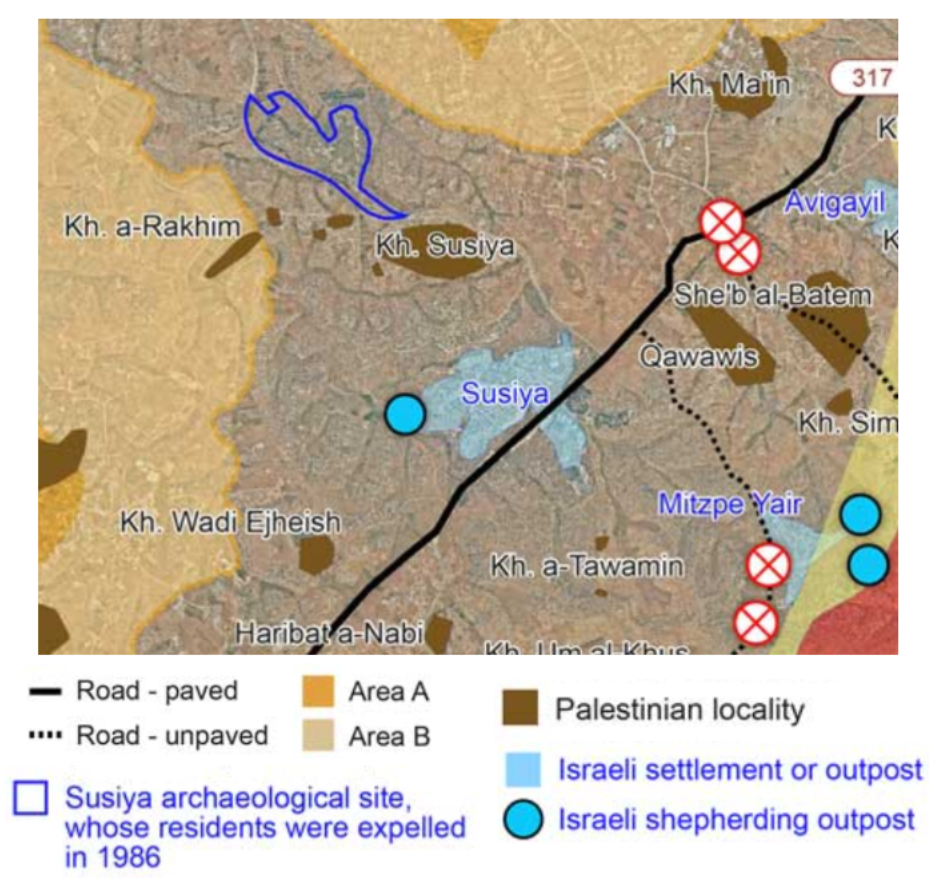

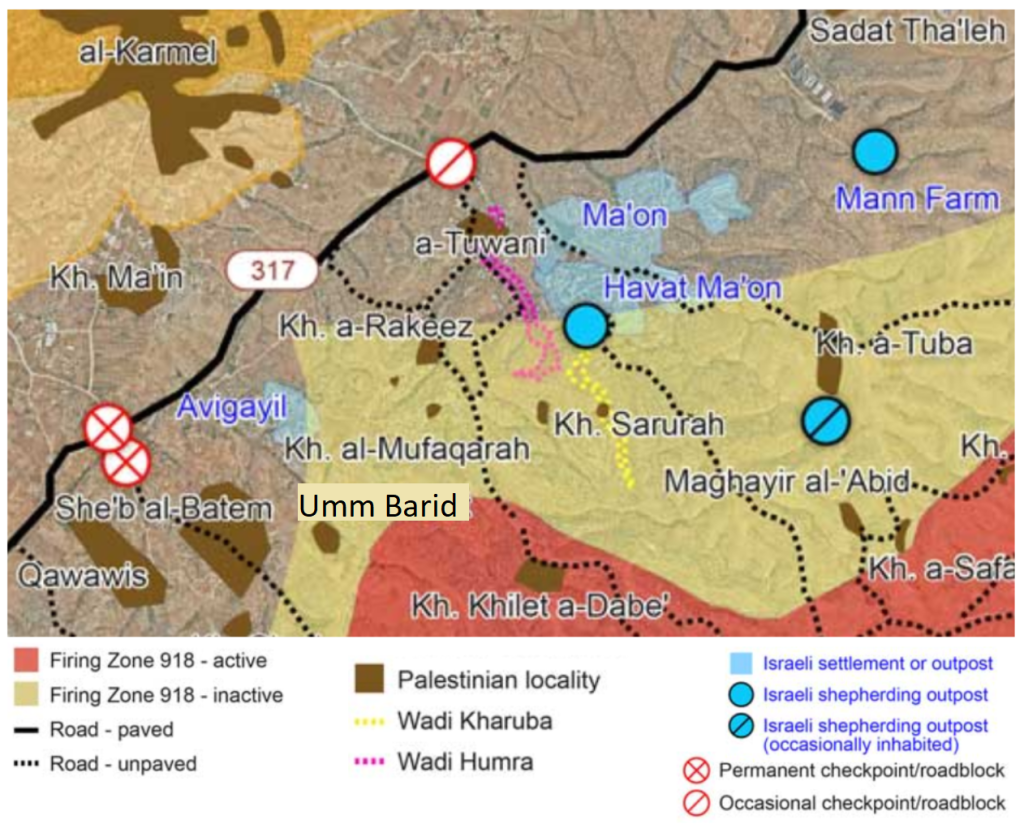

This week’s visits were to friends in north-central Massafer Yatta. A larger map of Massafer Yatta can be found here. To see the broader surroundings, go to B’Tselem’s interactive map and zoom towards the very south of the West Bank.

At the beginning of the Gaza war the family members of the late Harun – a young man shot in the neck by a soldier on 1.1.2021 while trying to stop soldiers from robbing his family’s generator and who passed away almost a year ago after two years of suffering – left their home in Rakeez and moved to the regional urban center of Yatta. They did so because, as we and others have been documenting online, relentless settlers with the full backing of Israel’s government, judiciary and military have been exploiting the terrible massacres of October 7th as a pretext to accelerate the multi-pronged ethnic cleansing of West Bank Palestinians, with particular focus on Massafer Yatta. These settlers and in effect the entire state apparatus, have declared war in a place where there is not even an enemy.

This is why Harun’s family escaped to Yatta. But last week they returned to Rakeez! They missed home; Yatta did not grow on them. Their sheep, too, wished to return to their pastures which have now greened after the fall rains. They know that the aggressive behavior of Occupation forces, which during the war have become a military-settler amalgam, has only escalated – and yet they have returned. This way, they can at least start restoring the vegetable patch, the sheep will graze on some grass and provide milk. There will be some food somehow.

But the area’s settlers, who are now the official regional military “emergency squad” with uniforms and military weapons, keep trying to prevent local farmers from tilling their own lands and grazing their own herds, and threaten the farmers’ lives continuously. The Israeli public and the world have turned a blind eye on the injustices committed here for years, and Harun’s family had already paid a dear price. In 2021 as now, there is no war in Massafer Yatta. [only injustice]

We visited the family last week, and for us too it felt like a homecoming. During our visit R. was with the sheep together with his 7-year-old daughter D. While we enjoy the visit (we have not seen the family since the war started), we were told that an armed settler appeared in the family fields. We did not go there in order to avoid providing a pretext (Occupation forces dislike “leftists” as they call us). R. returned with the sheep, who remained hungry that day.

We then visited S. and his family, also in Rakeez. They have not left their home, but during the war they have been suffering from ongoing encroachment on their lands, and intrusion into their living spaces. We have witnessed this before. The few residents of Rakeez who still live at home and till their lands go to bed in fear, wake up in fear every morning, go about their entire daily routine in fear – and when we come and visit, they tell us that things will surely get better soon. Indeed, they are such “a dangerous enemy” [that is, an enemy” according to the dominant media-political-military narrative in Israel, a narrative attempting to justify the injustice by demonizing all Palestinians everywhere].

We continued down the road to A-Tuwani, where we visited Zakaria again. As we wrote last week, Zakaria was shot in October by a settler and spent three months in a hospital in Hebron/Al-Khalil. In another three months Zakaria will undergo his 12th surgery, this time in an effort to restore his digestive system. Until then, he needs more than 100 sterile treatment kits, available only in hospitals. The Al-Khalil hospital discharged him with only three kits. A wonderful doctor from Israel’s Sheba hospital (near Tel-Aviv) has helped us yet again, providing more kits. There are still good people one can find along the way, and they help provide light especially in such dark times.

Over the weekend we visited M.’s family from Umm Barid. That’s the family whose home and entire belongings were destroyed by settlers in October-November in repeated attacks. They still persist and persevere with restoration attempts. They live in a small house donated by a neighbor in nearby Sha’ab al-Butum. They too were mentioned in last week’s report, with the picture of a dove’s first flight we had brought them. Settlers from the nearby outpost are still strolling around the home and greenhouses which are undergoing gradual restoration, and around the fields which have been sowed.

We visited the family in their temporary Sha’ab al-Butum home. No one knows what tomorrow may bring, but they are full of faith. “After all, I have now coordinated with the military [for protection]” says M. with shining eyes. Meanwhile we brought them some coloring books, designed both for children and adults. Even before I start explaining that Mandala coloring is a type of meditation, M.’s eldest son S. who is father to the four young children running around as we spoke, told me: “This is truly like a doctor for the soul, please bring me one as well next time.”

I smiled to myself and recalled the well-known Zen parable, here is one of its many versions:

A man walks along the road and suddenly notices a tiger chasing him. He runs as fast as he can and jumps to hang on a tree trunk by the roadside in order to escape the tiger. As he tries to catch his breath, he notices that the trunk in fact hangs precariously above a deep ravine, at the bottom of which growls another tiger. While he tries to improve his grip on the tree trunk, the man notices two giant rats gnawing away at the base of the trunk.

So: a tiger behind, a tiger below, and two rats gnawing away at his last chances of survival. In that very moment, the man notices a grape vine growing from the side of the cliff near him, bearing fruit to a bunch of grapes. As he maintains his grip in one hand, the man reaches out his other hand and picks the bunch. He eats the grapes and says to himself, “How delicious!!!“

Erella on behalf of the Villages Group [translated by Assaf Oron]